The turmoil in the credit markets in the U.S. is going to have major impacts on the size and number of private equity deals for the foreseeable future. It will be a painful process for the general populace as well as investors. The pool of PE funds and the sources of debt for LBOs will shrink in the U.S. and Western Europe. But all of these changes will prove to be a minor blip in the growth in private equity.

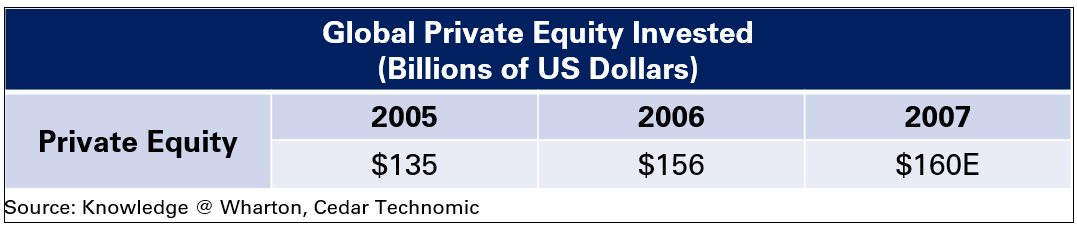

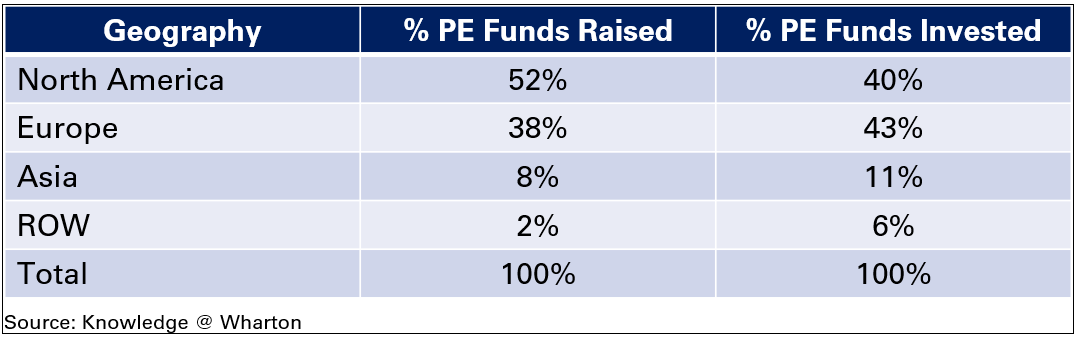

Amid all of this turmoil, there is an underlying fact about private equity: it is still a situation of more money chasing fewer deals, particularly in the developed countries. For example, in 2005 private equity investments totaled $135 billion, but the total amount of private equity raised totaled $232 billion. The gap is made up of draw-down commitments and “under-invested" assets. This large gap has since declined but is still significant. It is a combination of smaller deals and fewer investments. The main culprits are that there are fewer bargains, e.g., undervalued companies and fewer attractive startups, but there are several other issues at work. Debt for LBOs is no longer as readily available as it was before the subprime mortgage debacle. Another one is the relatively low level of private equity activity in Asia and the rest-of-the-world (including South and Central America). These regions account for only 10% of private equity funds raised and 17% of private equity invested.

On the other hand, many of these economies are as large as or larger than most European economies and their GNP growth rates are 2-3 times greater than those in North America, Japan or Western Europe. Do companies in Asia and the rest-of-the world need sources of capital? Of course! Can these companies generate the kinds of returns that private equity investors expect (e.g. 30% average historical return)? Maybe…

The biggest barriers to an explosion in private equity placements outside of the developed world appear intractable at first glance:

Knowledge: Knowing the local markets, companies, governments, cultures and the environment is critical. Private equity investors are masters of quantitative analysis and risk acceptance. PE investors can quantify risks, but not uncertainties. Information in many developing countries, especially India, China and Brazil, is non-existent, incorrect or very old. While many of these countries have developed very large and active stock markets, the reporting of financial information is not well controlled or frequently checked for accuracy. The regulatory equivalents of the SEC do not exist or are ineffective. This dearth of good information makes valuing companies' worth and growth prospects in developing markets difficult if not impossible. Finding good companies to invest in is not easy either. There aren't large databases like D&B or others which can focus a search. Very often, as in China, the best companies may be unregistered and operating without a government license. They don't want to be found and may be very difficult investment vehicles for international PE.

Talented Managers: Looking at history indicates that the majority of private equity deals are not made for a quick profit. Their main strategic focus is to wring as much value out of the company as possible. This effort takes time and it takes good management. A key ingredient for any successful private equity placement is a pool of local management talent. In most PE deals, a team of managers will replace some or most of the incumbent management. However, the preference is to recruit the highest quality local managers who are familiar with doing business and dealing with the authorities. The demographics of developing economies represent a major challenge to private equity investors. The upper and upper-middle classes, which provide companies in the West and Japan with most of their management talent is very small in most developing countries. Many of these developing countries have very talented engineers and IT professionals, but the cadre of experienced executive managers and entrepreneurs is small and difficult to reach. Using expatriates is fine for the short-term but this approach is expensive and delays the inevitable need for good local executive managers.

Exit Strategy: Exit mechanisms are well developed in Western countries and Japan. Mergers, IPOs, ESOP/management buy-outs or recapitalizations are established exit modes with financial infrastructures and regulations supporting them. In developing countries, selling a company and repatriating the proceeds are often extremely difficult and expensive. Many of the financial institutions and laws that we take for granted in the West aren't the same in developing countries. Exit choices become very limited. Tax and ownership laws meant to protect a country's economy and currency result in difficulties for private equity investors. Once again, a special knowledge of the country's investment laws and tax and employment regulations is needed to profitability repatriate investments in these countries.

The solutions to these challenges all boil down to the form and depth of knowledge and due diligence that private equity firms are willing to undertake when looking at international growth opportunities.

Knowledge: Good information is no longer available off-the-shelf. Rather than relying on government data, required company filings and low-cost syndicated market reports that are readily available in the West, developing local first-hand knowledge is critical. The private equity investor has to be willing to invest in primary data collection and analysis of the target company, government regulations and cultural, religious and environmental issues. This type of due diligence is new to most private equity investors but is necessary to succeed in emerging markets.

Talent: Identifying and engaging top local management talent is a prerequisite to a successful investment. The cadre of local managers is very thin in most developing. An HR firm that is networked into the local economy and society is critical in most developing countries whether the intent is to hire a local executive manager or bring in an ex-pat.

Exit: New approaches to exit strategies in developing countries need to be in place well before a deal is structured. Special care is needed to respond to ownership restrictions, currency repatriation rules and taxes. Unlike most US and Europe regulations and tax codes, the laws change frequently and abruptly in developing economies. This volatility in the regulatory environment requires continual monitoring and repositioning of the investment.

Cedar Technomic expects to see more but smaller deals driving the private equity sector in the near future, especially in the international sector. The target companies will be more niched in terms of markets, products and/or geography. Private equity investors will need to re-think their standard due diligence practices, engaging more local outside help and working with primary data from non-public sources. These efforts will help to shift international private equity investments from uncertainty to measurable risk.

To read more such insights from our leaders, subscribe to Cedar FinTech Monthly View