Market research & competitive

intelligence can provide valuable

inputs for day-to-day tactics.

market analysis & competitive

analysis provides understanding

of the market’s and competition’s

dynamics and futures. what the

client wants to do and what

resources and talents will be

required within a market require

a full market assessment or

competitive benchmarking,

placing even greater demands on

the consultant’s knowledge.

You’re really a spy

My father would ask me, after I tried to explain to him what I did for a living, “You’re a spy, right?” Well, no, I’m not. I am an industrial market consultant. I collect information and interview people in certain technical markets and certain geographies and try to get answers to questions asked by my client. So, as my father would state after this explanation, “Then you really are a spy.”

Far from it. I am not collecting confidential or proprietary information under false pretenses. I am not misrepresenting what I am doing. I am not collecting or using this information to cripple or destroy my client’s competitors. But, what am I doing? At last count, I had been doing it for 35 years, so I should know by now.

“Those who can’t do, teach. Those who can’t teach, consult.” One of my favorite sayings. We go into markets to provide our clients with accurate and detailed descriptions of how big a market is, how fast it is growing, its key segments, channels, the competition, and the technologies and identify trends and how they will impact the future of this market. All well and good, but these data are almost all available today for free on the Internet or through a low-cost data research report. But, we do not stop there. We answer the “WIIFMS” question developed by my early mentor, George Plohr: “What’s in it for me, stupid?”: The “So What” Question. We provide our clients with a context of accurate and timely market and competitor data and insights so that current and future opportunities and threats facing our clients can be understood, good decisions can be made, and actions can be effectively implemented: Good information and insights lead to strategies that work.

Understanding your markets

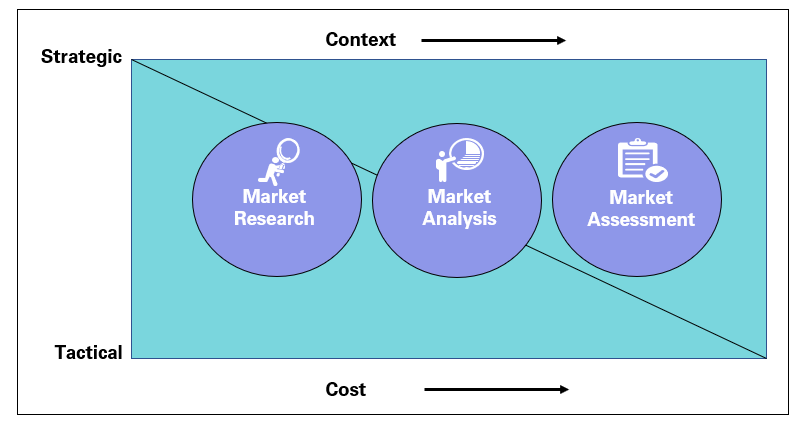

As a former secretary of defense once said, (in abbreviated edited form), to justify invading Iraq for weapons of mass destruction, there are known knowns (we know what we know) and known unknowns (we know that we do not know some things) and unknown unknowns (we do not even know we do not know some things). For businesses, what always trips them up are the last two unknowns. As my high school English teacher once said to a parent of a struggling student, “Not only does he not understand the material, he doesn’t have a suspicion.” Looking outside at the market is critical to adding to a business’ “knowns” and reducing the number of “unknowns,” both the known and even the unknown types. These approaches to understanding your markets are a continuum of research and analysis techniques:

- Market Research

- Market Analysis

- Market Assessment

Market Research

Market research is an effective methodology to quickly and inexpensively learn about a market’s current size/ value, basic segmentation, structure of channels and supply chains, and customer preferences. It is usually done through the acquisition of secondary data from Internet searches, government and trade publications, and quantitative surveys of suppliers, distributors, and/or customers. Very often, databases are developed to track changes in past growth, segmentation, channels, and customer preferences. Market research is the foundation for all efforts to understand and effectively participate in a market. However, depending exclusively on market research is dangerous.

- Market research does not provide an understanding of market dynamics and interactions between participants. It is a very static view of a very dynamic environment.

- It usually does not do a good job of predicting future outcomes of the market, technologies, government regulations, and actions by the competition. It uses the past as a predictor, almost always missing the impacts of major disruptors such as new technologies, new products, and new competitors.

- Database data tend to only accurately reflect past performance of a market, often using obsolete assumptions. Market researchers who use databases tend to dislike making changes that would compromise everything they have done or said in the past. A database has a life of its own and tends to evolve further from reality the longer it is used.

Market Analysis

Market analysis brings us a step closer to really find out what is really going on in a market. In addition to using “market research,” described above for secondary information and generally held opinions, it goes one more step, collecting primary data (e.g., interviews) from people who actually participate in a market, whether they are executives, marketers, engineers or distributors, suppliers, and competitors. The process of collecting primary data allows the consultant to understand the intricate workings of a particular part of the market: how prices are set, how products are made, to whom they are shipped, who the intermediaries are, what margins are along the supply chain, who has entered the market, who has left it, what new technologies and approaches are being used, and most importantly, what is changing or different from the past in the eyes of the respondents. Market analysis provides an understanding of the mechanisms of how a market works at different levels and how it is changing. Market analysis brings the future into consideration and helps clients understand how the market is expected to evolve. Market analysis has its limitations and challenges too.

Consultants use legal and ethical techniques that can provide clients with useful competitor information and insights.

- The education, intelligence, discipline and rigor of the consultant are critical. Primary interviews in one segment or one channel, at the exclusion of others, can often bias the results and make them less valuable to the client. Having the technical understanding and acumen of the particular market is also important in understanding what the respondent is saying. It is the old story of the blind men touching the elephant. One thinks it is a snake, the other a large tree, etc. The consultant needs a holistic perspective on a market to provide the client with an accurate and useful understanding.

- Taking the qualitative information from primary interviews and turning it into accurate quantitative information is an art form with some science behind it. The consultant must act as an interpreter during the interviewing sessions to convert spoken “analog” data into defensible and accurate printed “digital” data. This process requires an understanding of logic,statistics, limiting degrees of freedom, and in some cases, integral calculus to arrive at an accurate translation of the interview.

Market Assessment

"Phylogeny recapitulates ontogeny” is a famous, if somewhat discredited expression in biological circles, but it is accurate as a description of what happens as market research evolves to market analysis and then to market assessment. Market assessment takes everything done in the two previous examples and adds the client’s business as a variable in the analysis of a market. Market assessment provides the context of the client’s resources, talents, and capabilities into a description of how the future market is likely to look. It begins to answer the “WIIFMS” question raised at the beginning of this discussion because it takes the information, analysis, and insights gained and puts them into the context of the client’s business.

What is the best approach?

Selecting the most appropriate approach to obtain market information depends on the questions the client asks and how the information will be used. Information through market research can provide valuable inputs for daily tactics or as a check on what is going on in a market as a “snapshot.” Understanding the market’s future requires more in-depth analysis and primary interviews. Finally, what the client wants to do and what resources and talents will be required within a market requires a full market assessment.

Understanding your competitors

Consultants of all stripes, including those worn in prisons, provide some form of service to supply clients with information about their competitors. Competitive information is a subset of the market information gathering techniques described above. In the US, information that flows directly between competitors is restricted by internal management policies as well as Federal anti-trust and anti-collusion laws. Technical conferences, trade shows, association committees, and academic papers are venues where some direct communication occurs, but the material is usually completely redacted and the presenters well briefed on what they can and cannot say publicly. The indirect methods are those we are familiar with: government data, web searches, and purchasing low-cost syndicated market studies with the hope that these will result in a few nuggets of competitor information. All the activities above can be done by the company’s employees seeking competitor information. These activities are legal and ethical but not very effective.

Third-party consultants are often called in if a client wishes more information on the competition. Consultants use legal and ethical techniques that can provide clients with useful competitor information and insights. However, sometimes they also use techniques that are neither legal nor ethical. After a lifetime of consulting, I have heard them all. Here are a few in my “Consultant’s Hall of Shame:”

- A technical guru posing as a potential (but naïve sounding) buyer at a trade show and a conference

- A company employee posing as a consultant with a false name and contact information

- Phantom employment advertisements in the local area newspaper where a competit

- Intercepting WiFi transmissions

- Aerial photography (legal in Europe but not in the US)

- Dumpster diving (too many cases to mention)

- Posing as a graduate student working on a thesis (or using real graduate students) And my favorite.

- Pretending your car is broken down and knocking at the back door of a competitor’s factory for help (his car wasn’t broken down; neither was his camera).

The above mentioned examples fall under industrial espionage and (if not completely illegal) are totally unethical. There are many ways of doing it right. Consultants can interview suppliers, distributors, customers, and other competitors in a straightforward and ethical manner. Obtaining competitor information from government agencies, such as courts, the Environmental Protection Agency, municipal zoning and planning departments, and other public agencies, is legal. Discussing competitors with financial analysts (if they are tracked) and other third-party observers is also a route used by consultants. But we believe that the most effective approach is completing multiple levels of primary interviews with the target competitors and others. Information on competitors falls into three categories, which are defined by the information requested by the client and how the information will be used. These categories are as follows

- Competitive Intelligence

- Competitive Analysis

- How many refrigerators are shipped per truckload?

- Competitive Benchmarking

Competitive intelligence

Competitive intelligence (CI) has a bad name because it is often associated with industrial espionage. This image of “CI” is due to the competitive questions it is supposed to answer. These questions are usually single-point facts of often sensitive information. For example,

- What is the cycle time for a specific injection molded component?

- What temperature is the can of baked beans cooked on the production line?

- How many refrigerators are shipped per truckload?

- What is the tablet model’s most frequent failure mode?

- Does the competitor’s supply contract include minimum annual volumes?

The answers derived from CI are used for near-term tactical purposes by the client, e.g., to fine tune a process, strengthen a contract bid, or provide salespeople with “ammunition.” In most cases, the information impact is short-lived and focused. CI efforts are targeted for short duration and relatively low cost. Practitioners of CI cover the full range of consulting firms, but the CI staff usually includes ex-security, military, FBI, or police personnel.

CI is a useful tool but provides little context. It generates single, isolated data points that lack any context or predictive value and cannot answer the “WIIFMS” questions we discussed earlier.

Competitive analysis

The next type of competitive information acquisition is competitive analysis. The information collected and analyzed is at a higher level than CI: segment sales revenues, market shares, strengths and weaknesses (SWOT analyses), apparent strategies, and financial performance. Rather than a single point of competitor information, it can cover sales, manufacturing, technology, HR, and financial functions. Although having less depth than CI, competitive analysis provides a context that allows clients to compare the target competitors with themselves or others. Questions covered in a typical competitive analysis program may include

- What are company X’s, Y’s, and Z’s sales and profitability in a particular market segment?

- How has company Z’s share changed?

- Is company X entering a new market with their new product line?

- Who are the biggest players in our served markets?

Competitive analysis is usually used to formulate business unit and corporate level responses to competitor actions and plans. It is also used extensively by private equity firms trying to understand a market’s competitive environment and their target’s position in it. This approach is open to greater interpretation but does a better job of answering the “so what” question for the client than CI alone.

Competitive benchmarking

Another form and use of competitive information is competitive benchmarking. Very often a competitive benchmarking exercise is as detailed as a CI exercise but it covers a broader range of functional issues such as those covered in competitive analysis: marketing, sales, R&D, distribution and logistics, and manufacturing and management processes. Its purpose is different from CI or competitive analysis because it is ultimately an inward looking exercise. Competitive benchmarking is intended to help the client establish factbased benchmarks for performance and measure its performance against other competitors. The main purpose is to make internal changes to improve performance. Benchmarking requires the collection of accurate competitive information and the development of consistent measures. Examples of questions that competitive benchmarking answers are:

- What is our sales effectiveness based on sales per employee and total sales per product category?

- Are SG&A expenses as a percent of revenues in line with our industry?

- What is our energy cost per unit output and is it better or worse than our competitors’ costs?

Competitive benchmarking provides a clear context for the information: the client’s organization. Benchmarking can be further used as an input to a Balanced Scorecard analytical approach to improve performance and correct problems. It has a long-term impact on the organization.

What is the best approach?

Competitive information can provide valuable inputs for daily tactics or strategy formulation. Clients need to know what questions need to be answered before going outside to a consultant. Selecting the most appropriate approach depends on the questions the client asks and how the information will be used. If it is just a general fact gathering on the competition, CI is the way to go. But, for a greater understanding of the competition, and most importantly, what the client could do, competitive analysis and benchmarking are the best alternatives.

Conclusion

The value and effectiveness of any work done by consultants is dependent on clients’ knowing what questions to ask and what answers they are seeking. It is also important that clients realize that there are “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns” that will impact their businesses in the future. It all comes down to selecting the right consultant for the job. A consultant’s functional expertise and subject matter expertise become more important as the decisions to be made and directions to be taken become more important to the client. One size does not fit all when it comes to selecting consultants to help clients understand their markets and competitors.

To read more such insights from our leaders, subscribe to Cedar FinTech Monthly View